From Passwords to Cloud SSO

When I was working as a software developer early in my career, back in the mid-nineties, there was no concept of Identity and Access Management as we know it today. We pretty much needed separate user accounts for every single application, workstation and server. There was no MFA with biometrics and such. Passwords and firewalls were the only methods to protect against unauthorized access.

During that time I discovered MIT Kerberos, which allowed for a single sign-on experience. In a nutshell, a user could obtain a service ticket—just an old-fashioned SAML assertion or JWT token—and use it to gain access to trusted services. It would also represent an initial implementation of a brokered trust model, which is at the very core of Federated Identity Management. Later, starting with Windows 2000, Microsoft adopted Kerberos as their security foundation, positioning heavily within the enterprise market.

Why didn’t Kerberos make it to the web?

Kerberos assumes that you are using trusted hosts on an untrusted network (typically within the perimeter). The Cloud broke those barriers, engaging with highly dynamic collaboration relationships involving partners, suppliers and even competitors. As hosts could be anywhere, coupling trust with the Kerberos requirements, as well as relying on a connection-centric protocol translated to a strong constraint for moving into the cloud.

The emergence of SAML

Security Assertion Markup Language (SAML) reflected the culmination of several standardization efforts around Federated SSO. The industry needed something aligned with the pillars of the Web, namely HTTP, XML and PKI. The first would be used for transporting identity assertions and the second and third to respectively represent, and secure those assertions.

As there were SAML implementations for virtually all the languages and platforms, it penetrated rather quickly in the B2B world. However, widespread adoption was limited by friction points such as poor interoperability among implementations, the lack of open source SDKs, and a steep learning curve.

From Apps to APIs

As SaaS point solutions started to gain popularity, securing the integration among them required something for which SAML was not designed. There were standards like WS-Trust and WS-Security meant to address these types of use cases, but those standards were missing the user consent pass in their workflow. OAuth was just what we needed for that. It allowed an application to act on behalf of the user upon consuming APIs serviced by another—potentially untrusted—application. All this without exposing credentials, and within a given scope in terms of allowed operations. OAuth was also focused on delivering an enhanced mobile experience, as well as playing nice with the emerging SPA (Single Page Application) web architectures. In order to achieve that, XML and SOAP—the building blocks of the WS-* standards—were replaced with JSON and REST respectively, which are still in use today.

OpenID Connect = stripped down SAML combined with OAuth

In mid-2010 reducing IT costs as well as shifting risks to a third-party became an even higher priority in the agenda of almost all CIOs. Sunken IT costs had to be drastically reduced and time-to-market with new services had to be increased exponentially, all while keeping hackers at a bay. The low entry barrier and ongoing maintenance, as well as the compelling cost model of SaaS seemed like a match made in heaven.

Since pretty much everything was becoming as-a-service, IAM had to join the club as well: Hello, IDaaS. No more setting up and maintaining identity infrastructure. But there was still a problem: SAML was not aligned with the demands of modern web and mobile application architectures, and OAuth was intended to address API authorization only. Moreover, IDaaS providers were pushing to achieve velocity by delivering an out-of-the-box experience for on-boarding clients’ applications. The way to approach that was to keep developers productive by giving them something familiar, and usable without too much hassle. OpenID Connect (OIDC) seemed to address all this and more. It grew on top of the IDaaS and social media waves capturing the consumer space. Although SAML is alive and kicking, it was relegated to the enterprise world.

Mind the gap

But what about enterprise applications that remained in the SAML era, and thus are not interoperable with OpenID Connect? Even worse, how about those that don’t support any standards-based Federated SSO at all?

The most common, non-intrusive solution is to use a gateway component sitting in front of an upstream OpenID Connect IdP, to act as an adapter for downstream SAML service providers. This is not a perfect solution because although both protocols share similar semantics, there are still substantial differences in terms of the corner case each addresses.

My personal take on this is that there has been a lot of reinventing the wheel. That reinvention has translated to the abandonment of pretty rock solid standards, for the sake of mass adoption and cost reduction.

So, we’ve turned on the time machine and performed a retrospective of the past two decades of Federated Identity. Of course, much more happened during this time—but I’ve opted to keep it simple and focus on what I think are essential events.

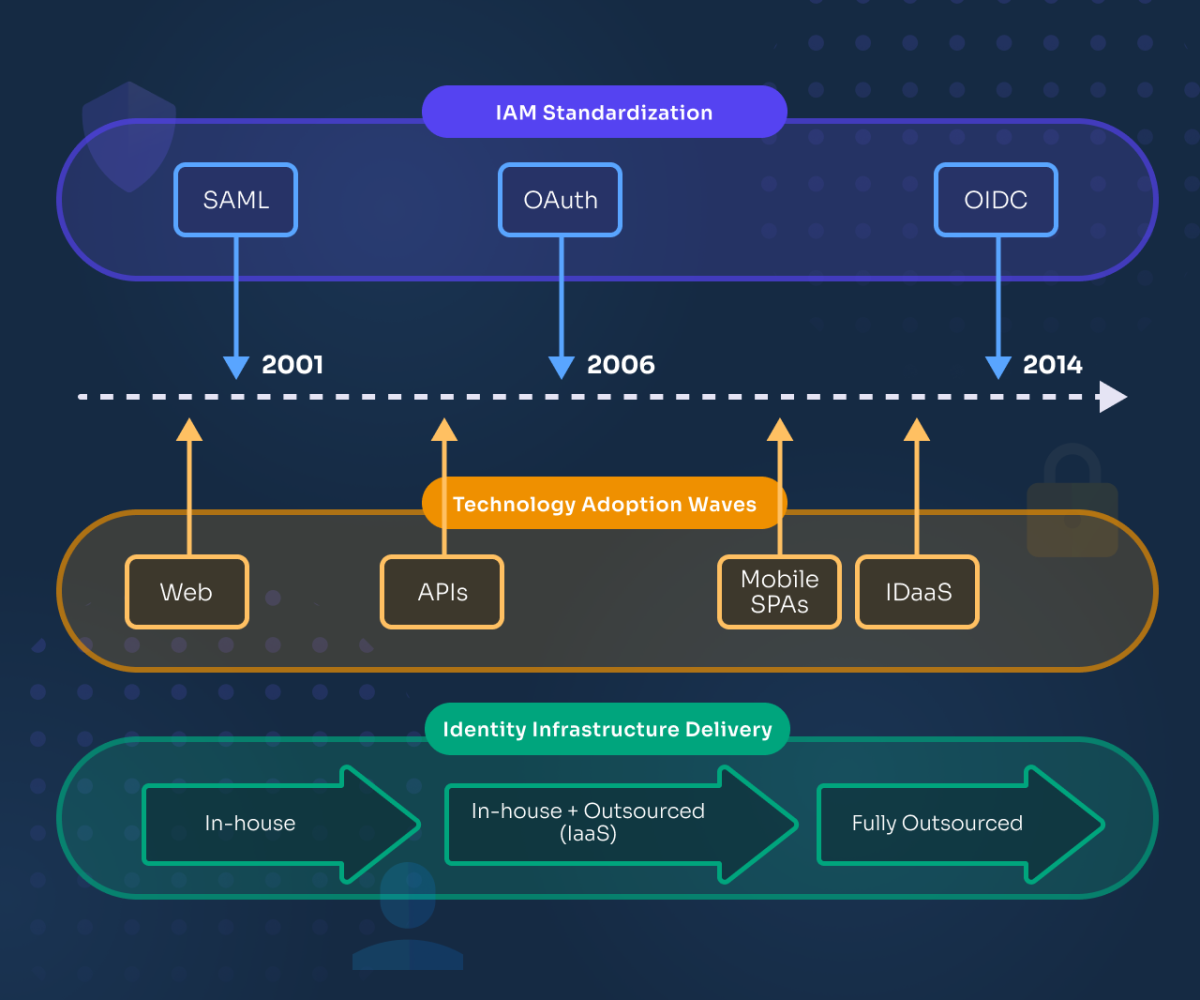

Bottom line, Cloud SSO was a by-product of multiple forces around standardization, adoption waves and innovation in terms of IT delivery models.

Password-less Cloud SSO

It’s worth noting that Cloud SSO doesn’t necessarily remove the need to juggle with passwords; it just allows users to enter them only once. In order to achieve a fully password-less experience, the Identity Provider has to include some sort of digital certificate-based authentication. The leading standard for this is FIDO, which I plan to explore in my next article.

Originally published on LinkedIn